As an American who grew up believing that the United States of America was the beacon of freedom in the world and that people all over the world envied our democracy and liberty, I could never understand why other countries would want to attack us. As a teenager, it was the Russkies and Chicoms that threatened us with their totalitarian aspirations. Today the threat comes primarily from terrorists, but hatred for our country seems to seethe from every corner of the globe. For many Americans, including me, this seems inconceivable. What motivated people all around the world to celebrate when the Twin Towers came down on 9/11? Why did so many dance in the streets and celebrate the worst attack on American soil in half a century?

As an American who grew up believing that the United States of America was the beacon of freedom in the world and that people all over the world envied our democracy and liberty, I could never understand why other countries would want to attack us. As a teenager, it was the Russkies and Chicoms that threatened us with their totalitarian aspirations. Today the threat comes primarily from terrorists, but hatred for our country seems to seethe from every corner of the globe. For many Americans, including me, this seems inconceivable. What motivated people all around the world to celebrate when the Twin Towers came down on 9/11? Why did so many dance in the streets and celebrate the worst attack on American soil in half a century?

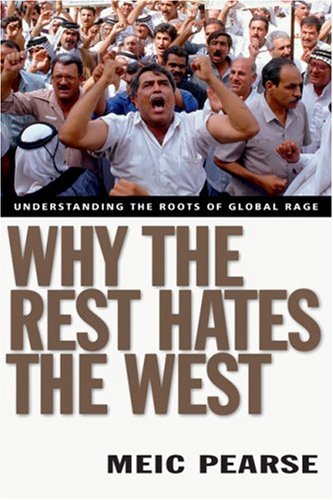

In his book, Why the Rest Hates the West: Understanding the Roots of Global Rage, Meic Pearse tries to help Americans understand the “roots of global rage” against Western democracy. In the introduction he views American tolerance, which many of us consider one of the cornerstones of our liberties, from another side. In this passage he is not referring to tolerance as moral relativism, but tolerance as the principles of freedom of religion, speech, press, etc.

The currency of the term tolerance has recently become badly debased. Where it used to mean the respecting of real, hard differences. It has come to mean instead a dogmatic abdication of truth-claims and a moralistic adherence to moral relativism—departure from either of which is stigmatized as intolerance.

Meic Pearse, Why the Rest Hates the West: Understanding the Roots of Global Rage (IVP, 2004), 12.

Christians decry this kind of tolerance, too, but we often fail to remember that this kind of moral relativism came from the West. We would rather imagine that we have only ever exported the virtuous kind of tolerance, which seems self-apparently superior not only to relativism, but also to the kind of restrictions on freedoms one finds in most of the world. How could anyone argue against the intrinsic goodness of a free democratic society? Pearse, however, describes the ability of tolerance to erode cultural and religious distinctives.

[Tolerance] is an agreement that a previously monolithic society makes with a minority: we will tolerate you and your strange ways for reasons that seem good to us (because we think it just, or because the advantages of doing so outweigh the disadvantages—or whatever) at the price of our overall culture being a little less sharply and rigidly defined than it has been before. Now, we agree to smudge the edges so that we can include you. (p. 11)

Pearse reminds us that many in the world see the impact of Hollywood, consumer culture, and crass capitalism (in contrast to principled capitalism) to be destructive to their culture. Instead of seeing the positive aspects of American culture that truly exist, many around the world are more inclined to see the glass half empty. It is hard to argue against the legitimate complaints concerning the corrosive power of American culture. Don’t we, in fact, preach against it in the church all the time? Why do we defend American culture against the rest of the world while we curse it in our own pulpits?

The truth is, the moral relativism that has been tolerated in America, especially in the last century, has invaded many countries around the world. Many of these countries had high moral standards, even if they were distorted and included practices we would find objectionable. Our relativism has worn away the edges of their cultures, captured the hearts of their young, and threatens their way of life. We may not agree with elements of various cultures around the world, but we certainly can’t deny that our “tolerance” has done this. And this is just one reason why many in the world hate the U.S. I don’t find the hatred completely justified, but the goal of this series of essays is understanding, not necessarily agreement.

0 Comments