Download The Free Guide

Discover practical conversation skills to get unbelievers thinking and make way for the Spirit’s work in their lives.

"*" indicates required fields

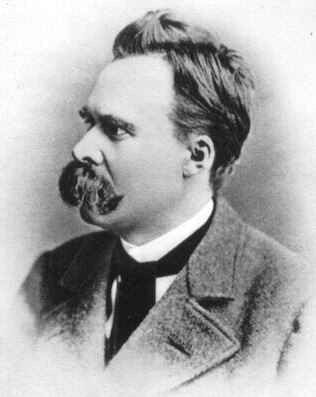

Nietzsche as Prophet Against Christianity

Nietzsche condemned Christianity for many reasons. His attacks focused on at least two themes that will be explored here—the death of God, and the life-denying character of Christianity. These are major themes under which other critiques may fall.[1] They essentially provide the substance of Nietzsche’s contrast between Christianity and the Dionysian life that he considered to be its successor. He summed up his philosophy in Ecce Homo: “Have I been understood? Dionysus versus the crucified…” (EH, The Case of Wagner, 9, p. 151). Shortly before he went insane, he reinforced this basic dichotomy. “Dionysus versus the ‘Crucified’: there you have the antithesis…the god on the cross is a curse on life, a signpost to seek redemption from life; Dionysus cut to pieces is a promise of life: it will be eternally reborn and return again from destruction” (The Will to Power, 1052, p. 542-3).

Nietzsche has probably written more against Christianity than almost any other philosopher or critic, and he is certainly the most vicious and blatant in his attacks. His anti-Christian diatribes are woven through almost everything he writes. Alistair Kee notes that while other things, such as music, were immensely important to him, religion was more fundamental to his life and thought. “It is possible to deal with Nietzsche while ignoring his thoughts on religion, but not without distortion. His critique of Christianity runs throughout the entire corpus of his writing. Loss of religious faith is the beginning of his journey, a loss which projects him against his will into a quest for an alternative faith by which to live.”[2] When Nietzsche was conceiving his own view of life and reality, Christianity always seemed to be the foil.

Nietzsche’s most infamous attack on Christianity is the parable of the madman (Gay Science, 3:125, p. 119-120). It is commonly held that Nietzsche saw himself as the madman. “Nietzsche prophetically envisages himself as a madman: to have lost God means madness; and when mankind will discover it has lost God, universal madness will break out. This apocalyptic sense of dreadful things to come hangs over Nietzsche’s thinking like a thundercloud.”[3] While Nietzsche says much about the death of God, the heart of his prophecy can be summed up in an overview of the parable. The death of God involves for Nietzsche at least three deaths.[4]

First, the God of the Christian faith is lost. That is, religious belief in a god just becomes too implausible. Second, the “god of the philosophers” died. This does not amount to much of significance since he had precious little content to begin with. The god of the philosophers was nothing more than “the most real being,” a concept too abstract to be useful. This was not really a god at all, but merely an idol “whose hollowness has been sounded out by Nietzsche’s hammer.”[5] Third, the Christ of faith is not an evangel, but a dysangel, a bearer of bad news. Speaking of Jesus, Nietzsche says, “Even the word ‘Christianity’ is a misunderstanding—there was really only one Christian, and he died on the cross. The ‘evangel’ died on the cross. What was called ‘evangel’ after that was the opposite of what he had lived: a ‘bad tidings’, a dysangel (The Anti-Christ, 39, p. 35).

The death of God as proclaimed by the madman is historic. Everything has changed. After the madman falls silent, he realizes that he was ahead of his time. “‘I come too early’, he then said; ‘my time is not yet. This tremendous event is still on its way, wandering; it has not yet reached the ears of men’” (Gay Science, Book 3, 125, p. 119-20). This event as proclaimed by Nietzsche himself is at the heart of his critique of Christianity, and even while he proclaimed it, he knew that its impact would not be felt to the fullest extent for generations.

The second reason for attacking Christianity was that Nietzsche believed that it was essentially an ascetic morality that was life-denying and harmful to instinctual passions. He saw Christianity as a reversal of values that needed to be reversed yet again, overturning Christian values. Alexander Nehamas notes that in his early writings Nietzsche “seems to urge that life must be unequivocally celebrated because, in contrast to the Christian view he rejects, he thinks that life is essentially pleasant, joyful, and good.”[6] Later, however, Nietzsche’s view of Christianity became subtler and more sophisticated. He treated judgments, whether positive or negative, as indicators of those who expressed them. Ultimately he saw all judgments as affirmative of something, so his question became, “of what is the judgment affirmative?” Nietzsche eventually came to attack directly “not any particular judgment but the very tendency to make general judgments about the value of life itself, as if there were such a single thing with a character of its own, capable of being praised or blamed by some uniform standard.”[7]

Nietzsche perceived Christianity to be nothing more than a morality, seeking to impose ascetic ideals on people in order to control their passions, and ultimately to control them. “One can see what it was that actually triumphed over the Christian god: Christian morality itself” (Gay Science, Book 5, 357, p. 219). With the death of God, nature would no longer perceived as proof of his goodness and care. History would no longer be considered telic. “That is over now,” said Nietzsche, “that has conscience against it; every refined conscience considers it to be indecent, dishonest, a form of mendacity, effeminacy, weakness, cowardice” (Gay Science, Book 5, 357, p. 219).

The end result of Christian spiritualizing of passions is castration, the cutting off in every sense, which Christianity considers a cure for the passions (TI, “Morality as Anti-Nature,” 1, p. 172). How can such a severe treatment of the body ever be accepted? Nietzsche reveals what he believes to be the process by which Christianity accomplishes the castration of the passions (The Will to Power, Book Two, 204, p. 121-2). First, one claims virtue for one’s ideal. Second, one’s own values become the standard. Third, one portrays any who contradict him as the enemy of God. Fourth, one attributes suffering to the violation of one’s values. Fifth, one portrays the natural instinct as contrary to one’s ideal. Last, one portrays the future consummation as the removal of all passion and instinct.

This is quite a remarkable claim by Nietzsche, and one hardly provable. But Nietzsche never set out to prove much, but rather to inspire thought through his bombastic style. So, the claims that God was dead and that Christianity was a life-denying religion were the cornerstones of his attack against Christianity. This raises an important question, “Was Nietzsche’s portrayal of Christianity accurate?” No one likes to be slandered, and if Nietzsche’s critique of Christianity is nothing more, then the force of his assault is blunted significantly. If, however, it can be demonstrated that Nietzsche was to some degree accurate in his critique, his words may be the dynamite that he thought they were.

In the next section, the nature of Christianity in Nietzsche’s day will be examined. It will be argued that European Christianity at the end of the 19th century was significantly different than historic, orthodox Christianity, and that as a result, Nietzsche’s critique of it rings true in many ways.

[1] Stephen Williams discerns three judgments on Christianity: it is intellectually impossible, it demeans humanity, and its morality is fatal to life. See Stephen N. Williams, The Shadow of the Antichrist: Nietzsche’s Critique of Christianity (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2006), 91-2. For the purpose of this essay, these three can be subsumed under the category of “life-denying.”

[2] Ibid., 7.

[3] Kaufmann, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychology, Antichrist, 97.

[4] What follows is the summary by Bruce E. Benson, Graven Ideologies: Nietzsche, Derrida & Marion on Modern Idolatry (Downers Grove: IVP, 2002), 75-6. Benson mentions four deaths, but the last two can be conflated into one.

[5] Ibid., 76.

[6] Alexander Nehamas, Nietzsche: Life as Literature (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), 134.

[7] Ibid., 135.

By Brandon Anchant, Intern In today’s Christian community, there exists a pervasive atmosphere of a pharisaical mindset. This mindset is characterized by...

By Brandon Anchant, Intern I was speaking with my friend Ralph at the climbing gym where I work. He is a sixty-something Englishman with a rather spicy...

5 Themes To Spark Faith Conversations INFOGRAPHIC How can we talk about Jesus in a way that connects with the people around us? Inspired by Dan Strange’s...